This Blog was first published on the HuffPost Blog on June 20, 2017

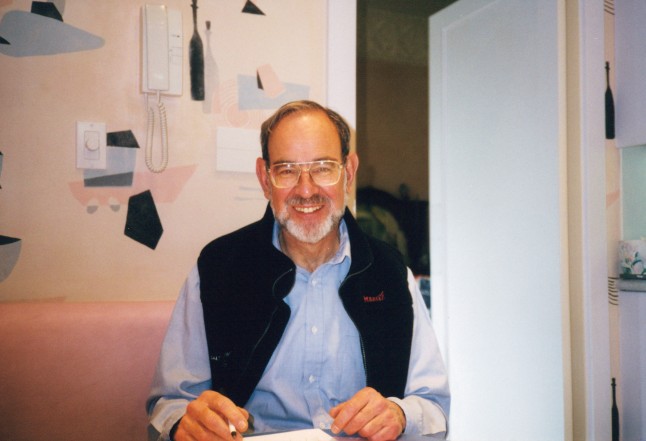

Love and hate often go together. I both love and hate writing to my father every week. When my stepmother placed him in an assisted living facility in 2014, I asked her if I could do anything for him in his new home. She suggested I send him cards. So for the last three years, every week I’ve mailed him a greeting card.

My parents divorced when I was six years old. For the first four years after their divorce, my entire family lived in New York City, and my brother and I visited our father, and later our stepmother, every other weekend. He never called us, but we felt connected to him through regular visitations.

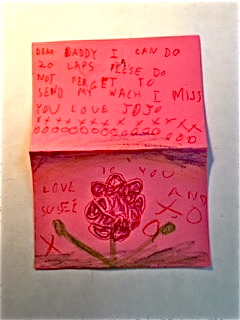

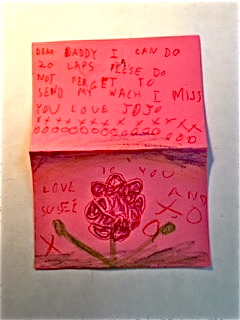

After four years, my father and step-mother moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, two thousand miles away, and our visits went from every couple of weeks to three times a year during school vacations. Both our father and stepmother wrote regularly. Their correspondence became our sole form of communication between season-long gaps in personal contact. After Dad and Suzy moved away, I spent every Sunday afternoon at my paternal grandmother’s home, where I wrote letters to Albuquerque. I’m a terrible speller, and I felt hugely proud of myself when I learned to spell Albuquerque correctly. This enabled me to address the envelopes to my father and stepmother without my grandmother’s assistance.

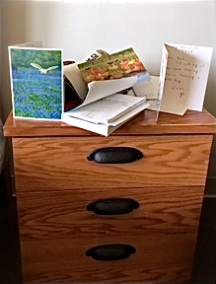

Less than a year after my father and stepmother moved to New Mexico, my mother, brother, and I also made a cross-country move to California. The letters between me and my family in Albuquerque continued. My grandmother had helped me establish my writing habit. During the last eight years of my childhood, I don’t recall receiving even one phone call from my father, but by the time I left for college, I had a huge stack of handwritten letters from Dad and Suzy.

Our letters evolved into phone calls when I moved to college, probably because I was then in charge of my own phone bills and could pay for the calls out of my college budget. My father and stepmother had established, and were largely funding, this budget.

When I was in my early thirties, a friend living in another state became acutely sick. I bought and sent a year’s worth of greeting cards to cheer her up. After the year ended, I replaced the cards with letters. I took pride in sending those weekly letters, and I hoped she enjoyed receiving them. This correspondence was entirely one sided, with no expectation of reciprocity. Our friendship was reciprocity enough. I ended this correspondence about fifteen years later when I became so sick, I missed two months of work. I simply couldn’t muster the stamina the letters required. After my health rebounded, I realized I’d burned out, and I stopped writing them. My friend didn’t seem to notice or care, but I hoped the fifteen years of cards and letters from me had brought her a small amount of pleasure.

I’ve also carried on a correspondence since 1979 with a childhood friend I reunited with in college. My friend and I rarely see each other or speak on the phone, but the correspondence is so intimate, I feel as if we’ve been having a thirty-eight-year conversation. Our letters are the bedrock of our friendship.

When Dad was first institutionalized, I tucked photos I’d taken in with the cards. I’d ask interesting looking strangers if I could photograph them, explaining my purpose. Two especially memorable photos depicted a baby in a straw fedora and a woman with rainbow-colored hair. I called it the Alzheimer’s Project, and no one ever refused my request. But over time, I realized Dad’s cognitive abilities had declined so significantly, he might not be able to understand the reason for the photos or the brief comments accompanying them. I expressed these concerns to my stepmother, who agreed that a simple message would now be all Dad could understand.

My greetings on the colorful cards I mail him weekly have simplified into two true sentiments: I hope you are enjoying your day and I’m thinking about you. Occasionally I check with my stepmother to ensure that the cards are still welcome. She assures me that Dad continues to enjoy them, and he shows them to her when she visits.

I hate sending the cards to Dad because they remind me of all that my family has lost—a brilliant, caring, and funny man who is now a remnant of his former self. But I love sending them because the cards allow me to care for Dad and connect with him through this small gesture, even if he no longer remembers who I am.

Dad established my life-long role as a letter writer, unintentionally setting the stage for our current one-way correspondence. I’ve been writing and publishing professionally since 2015. I’ve learned writing lessons too numerous to list here. But one of the most important things I’ve learned is to do my best and let go of the outcome. I’ll continue to write to Dad every week without any expectation of how my cards are received. This is a small part of the on-going process of letting go of my beloved father.

After my father died without warning, I often found myself crying suddenly. I cried while buying a cookie at a charity bake sale for a nurse who died in Iraq. I got choked up recalling how my high school class stood when our classmate who had cerebral palsy graduated, and became teary as I read about a homeless woman who died on the streets of New York City. At first I was embarrassed and perplexed by the waterworks. Over time I began to accept the unexpected crying as part of my grief process. We can’t always control our grief. Optimally we experience grief as it presents itself, feel it fully, and then let it subside until the next time it surfaces

After my father died without warning, I often found myself crying suddenly. I cried while buying a cookie at a charity bake sale for a nurse who died in Iraq. I got choked up recalling how my high school class stood when our classmate who had cerebral palsy graduated, and became teary as I read about a homeless woman who died on the streets of New York City. At first I was embarrassed and perplexed by the waterworks. Over time I began to accept the unexpected crying as part of my grief process. We can’t always control our grief. Optimally we experience grief as it presents itself, feel it fully, and then let it subside until the next time it surfaces

watch television. I didn’t want to talk to anyone or be productive. I simply desired to sit with my cats and miss my father. For two weeks, I gave myself permission to mourn in this manner, after which I felt ready to return to my usual life and its demands.

watch television. I didn’t want to talk to anyone or be productive. I simply desired to sit with my cats and miss my father. For two weeks, I gave myself permission to mourn in this manner, after which I felt ready to return to my usual life and its demands.